While I was a company First Sergeant in the Army, there was an acronym that became popular with my superiors: BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front). This was often used in non-official emails by the battalion commander or the Sergeant Major, and meant whatever guidance or communication being received was going to get right to the point, all other information and details pertaining would be underneath.

A few months back, my beloved Black people were complaining about the firing of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Air Force General C.Q. Brown, and are concerned about the elimination of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives for the entire Department of Defense.

Previously black folks had shown little to no interest in the black man in the military, and at times would even criticize black men for serving in uniform (mostly in the northern cities). Black love is always for singers and celebrities, athletes and radicals, and hoodlums, thugs, and anything destructive rather than constructive. In contrast, two months ago several of my black co-workers who decry matters of race were enthralled by the release of a high-profile NY criminal racketeer from prison. The current black indignation is false, it is not based out of concern for the black serviceman, because the African American in uniform rarely appears in or is considered by black culture created by black people. Do not confuse hatred of the president with love for black Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, Airmen, Coast Guardsmen, and Spaceforcemen (?).

Black love is chiefly for the worst among us, and will champion criminals, illegal narcotics dealers and the beloved ghetto street culture in film and song and rap and poetry. They will imitate his or her “swag” and lingo, while ignoring the African American in uniform. When in social circles and interactions, my black brethren, unless veterans themselves, have no interest in our military experience. Conversationally we don’t matter unless they can fish out something that may be used for their continual indictments of America, institutions, western society, whites, etcetera. When I don’t tell them what they want to hear, the conversation immediately switches to something else. What I have to say doesn’t matter.

My proof is that prior to this, most people didn’t know who General CQ Brown was, nor that he was appointed to Chief of Staff of the Air Force BY President Trump during his first administration—Same as the BLACK WOMAN President Trump promoted to Brigadier General in the US Marine Corps, Lorna Mahlock. Indignation at General Brown’s firing, and criticism of the change in DEI policy was not out of love for those of us in uniform, but out of hatred for ‘him’ (President Trump). Black people see the armed services either as just a job, probably taken due to lack of opportunity or to pay for college, or even because they think we are low IQ, and thus have little regard for us and what we do. Whichever the case, we’re not supposed to actually ‘believe’ in the whole military and American thing, we’re just supposed to milk it for a paycheck.

My proof is that prior to this, most people didn’t know who General CQ Brown was, nor that he was appointed to Chief of Staff of the Air Force BY President Trump during his first administration—Same as the BLACK WOMAN President Trump promoted to Brigadier General in the US Marine Corps, Lorna Mahlock. Indignation at General Brown’s firing, and criticism of the change in DEI policy was not out of love for those of us in uniform, but out of hatred for ‘him’ (President Trump). Black people see the armed services either as just a job, probably taken due to lack of opportunity or to pay for college, or even because they think we are low IQ, and thus have little regard for us and what we do. Whichever the case, we’re not supposed to actually ‘believe’ in the whole military and American thing, we’re just supposed to milk it for a paycheck.

But as a people we believe in and ‘luh’ dem streets. We have deep concern about our wayward youth but then ensure that the best examples of blackness are left out of the culture. For instance, actor Jonathan Majors filmography when described by blacks always leaves out “Devotion”, in which he portrays Lieutenant Jesse Brown, the United States Navy’s first black aviator and combat pilot. Also left out is his first feature film appearance as a Union Army corporal alongside Christian Bale in “Hostiles.” Neither film was brought to us by a black director, who prefer films about the streets and then insist that it is white Hollywood promoting negative stereotypes. See my essay titled, “Are We For or Against Drugs” in which I pointed out that most of my black peers preferred TV show “The Wire” over “24”, the former about the drug trade in Baltimore, exclusively black, while the latter portrayed Dennis Haysbert, African American–as president of the United States.

Review all of the films made by black directors and show me the portrayal of black men in the military, and do the same with your music, and your poetry, your sporting events, and your overall culture. Recall the ‘Friday’ films by Ice Cube (what is his real name?), any ‘black’ television shows, any Tyler Perry production, anything out of black culture, and black men or women in military service do not exist. It occurs rarely and when they are shown, tend to show us in uniform as misled, disillusioned, and suffering—not as respected champions.

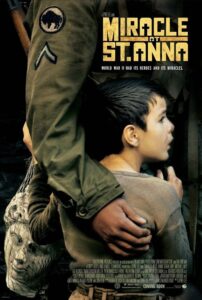

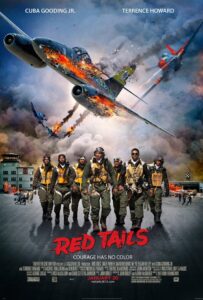

A LONG time ago, there was “A Soldier’s Story” with the all-star black cast of Adolf Ceasar, Howard Rollins from “In the Heat of the Night” and a very young Robert Townsend and Denzel Washington, among others.  In film, the only black director to portray the black man in the military was Spike Lee’s “Miracle at St. Anna” and “Da Five Bloods”, and the underfunded “Red Tails”, by black director Anthony Hemingway. Bill Cosby’s

In film, the only black director to portray the black man in the military was Spike Lee’s “Miracle at St. Anna” and “Da Five Bloods”, and the underfunded “Red Tails”, by black director Anthony Hemingway. Bill Cosby’s

show “A Different World” featured an ROTC commander, Colonel Taylor played by Glynn Turman, but did anyone else question that NONE of the students were one of his cadets?.

show “A Different World” featured an ROTC commander, Colonel Taylor played by Glynn Turman, but did anyone else question that NONE of the students were one of his cadets?.

Black Soldiers of World War 1 were depicted in “Roots: The Next Generations”, and a Mario Van Peeples film titled “Posse” that was more about a robbers errand than the men’s military contribution.

The most notable films that portray blacks in the military come from white directors: “Glory,” “Devotion,” “Red Tails,” “Emancipation,” with Will Smith, and “Apocalypse Now,” which features a barely adult Laurence Fishburne and Albert Hall (Bro Baines from Malcolm X).

It seems that white directors have changed and opened up to black men in uniform more than black directors have.

Their portrayals of us black men are no longer prop-like but of contribution and gallantry and honor and technical expertise—who can forget Denzel and Rocky Carroll in “Crimson Tide”?

I visited Washington D.C.’s National Harbor Convention area, teeming with revelers and restaurants and specialty shops and stores, some of which advertise African American ownership and products. Entering one, there were racks of hooded sweatshirts emblazoned with the words, “you can’t erase our history.”

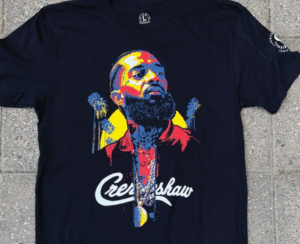

I visited Washington D.C.’s National Harbor Convention area, teeming with revelers and restaurants and specialty shops and stores, some of which advertise African American ownership and products. Entering one, there were racks of hooded sweatshirts emblazoned with the words, “you can’t erase our history.”  I found this ironic because none of the history alleged to being erased appeared on any merchandise in the shop, the Obamas the only exception. There were posters of murdered rappers Nipsey Hustle, Popsmoke, Biggie Smalls, Tupac, sweatshirts with Bob Marley with a joint hanging from his mouth, Snoop Dogg in a cloud of smoke . . . Gen. CQ Brown was nowhere to be seen, nor any other black person in a military uniform. But “they” are erasing “our” history.

I found this ironic because none of the history alleged to being erased appeared on any merchandise in the shop, the Obamas the only exception. There were posters of murdered rappers Nipsey Hustle, Popsmoke, Biggie Smalls, Tupac, sweatshirts with Bob Marley with a joint hanging from his mouth, Snoop Dogg in a cloud of smoke . . . Gen. CQ Brown was nowhere to be seen, nor any other black person in a military uniform. But “they” are erasing “our” history.

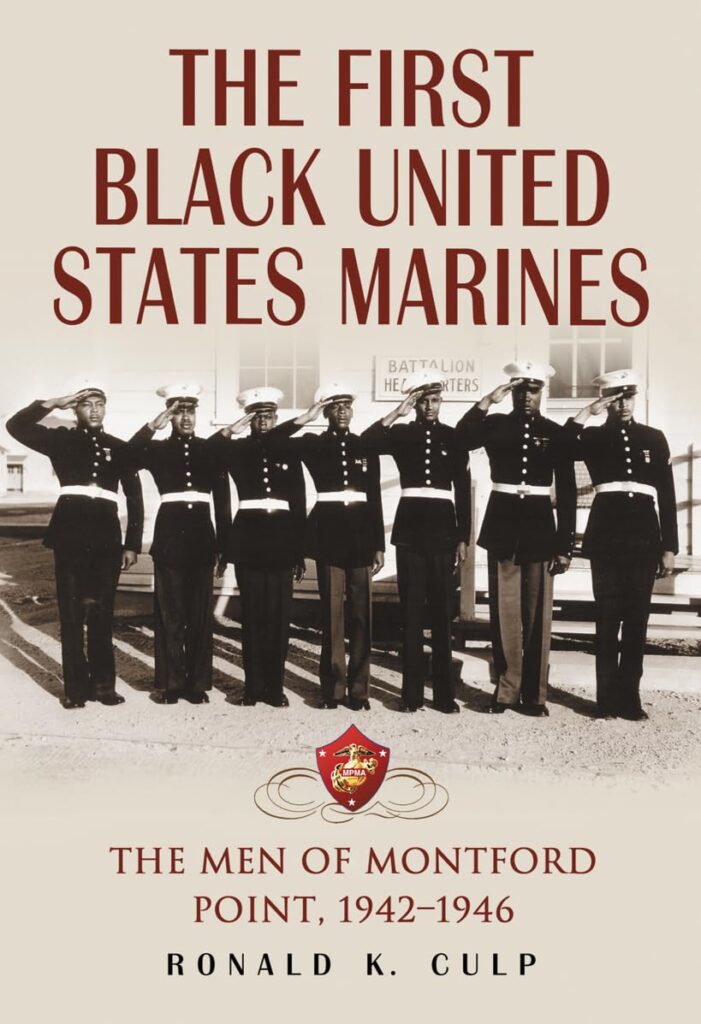

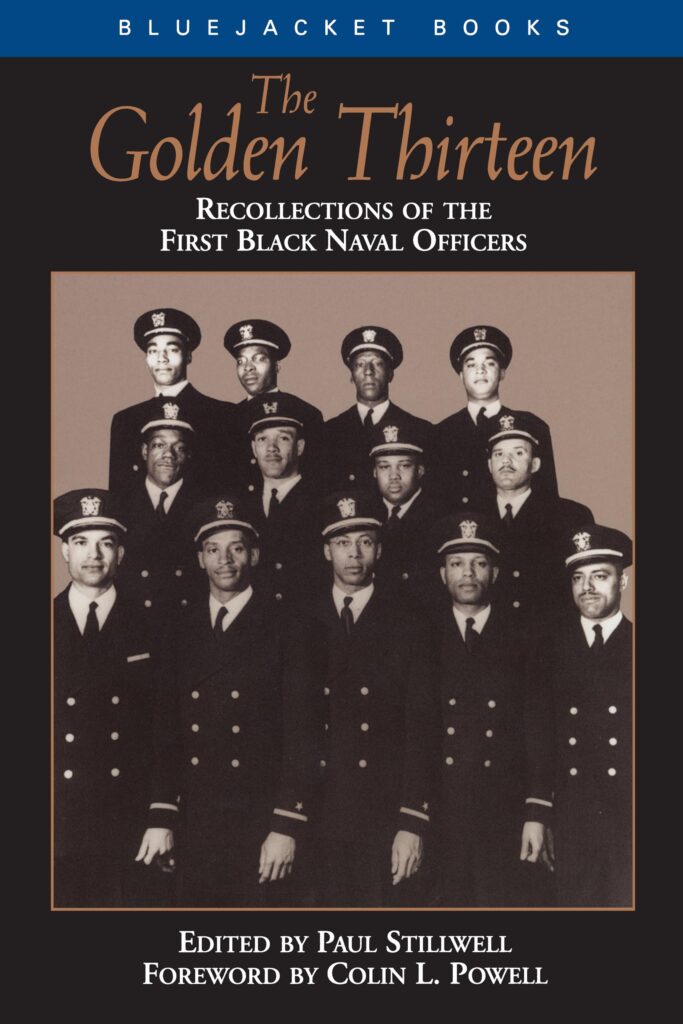

The bookstore next door was somewhat better, stocked with books written by high thinkers, but every book seemed to be about race. Scanning the titles on the shelves, no other topic was visible, just race-based work

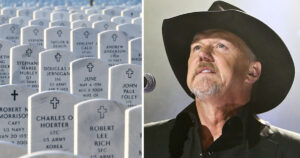

American film will depict its Soldiers and Marines and Sailors and Airmen (not much Coast Guard) and we never forget those in uniform at events and during holidays. I have a playlist of music that shows reverence for my millions of peers and myself; none of it produced by a black artist. Country music always remembers the Soldier: I was introduced to it by the Army, or more specifically, some Soldiers from Kentucky who were listeners of that genre. I grew to it and noticed in particular that almost every country artist showed a great deal of admiration and love for the military and some had served themselves.  One of my favorite military themed songs is “Rooster,” by grunge rock group ‘Alice in Chains,’ written by lead singer Layne Staley about his father who served in the Army in Vietnam. Another is “Arlington” by Trace Adkins, above.

One of my favorite military themed songs is “Rooster,” by grunge rock group ‘Alice in Chains,’ written by lead singer Layne Staley about his father who served in the Army in Vietnam. Another is “Arlington” by Trace Adkins, above.  Then there is “Dress Blues” by The Zac Brown band, and “American Soldier” by Toby Keith. The list goes on, it is common for country music and sporting events to remember us in the uniform and make it central to the culture

Then there is “Dress Blues” by The Zac Brown band, and “American Soldier” by Toby Keith. The list goes on, it is common for country music and sporting events to remember us in the uniform and make it central to the culture

When I was still in uniform, any recognition I received came from non-black people except for veteran’s day, during which a black person who was also a veteran or had a relative in the military would then speak positively. It is then black folk will admit some level of respect, but the suggestion that we are tools of America and white people’s ambitions doesn’t come long after. Or, the question that offended me which would be uttered after looking around and then uttered to me in a low voice: “So when you gettin’ out o’ that sh**? You must be sick of them by now.” Or after I retired, a good friend exclaimed “Good!” and given his political views I knew that it wasn’t just a celebration of my completion of service but also his disdain at it.

When I was still in uniform, any recognition I received came from non-black people except for veteran’s day, during which a black person who was also a veteran or had a relative in the military would then speak positively. It is then black folk will admit some level of respect, but the suggestion that we are tools of America and white people’s ambitions doesn’t come long after. Or, the question that offended me which would be uttered after looking around and then uttered to me in a low voice: “So when you gettin’ out o’ that sh**? You must be sick of them by now.” Or after I retired, a good friend exclaimed “Good!” and given his political views I knew that it wasn’t just a celebration of my completion of service but also his disdain at it.

So, when I hear this sudden concern for an African American in the military, I see it as fake love. It is even a loose intersectionality, which I discussed in an essay I wrote a couple years back. Intersectionality is a fancy word for using people. This is done under the guise of a supposed common goal, but you don’t care about us a bit…you complain not out of love for us, but hatred of him

But I want to look at some of what got us here, and these are the details and information.

During the Revolutionary War, the British and Continental Armies were dogged by interpersonal beefs and competition between peer commanders that led up to the betrayal by General Benedict Arnold. During the Civil War, the Union army was disastrously commanded by a series of officers who were political appointees, resulting in two years of horrible bloodbath losses at the hands of the smaller, lesser equipped, and better led Confederate army. During the early years of World War II, the US Navy was outfought by the Japanese in several battles due to Japanese proficiency and (in my opinion) arrogance at a people white commanders saw as inferior. Vietnam was the obvious and well-documented incoherent battle plan formed out of arrogance, confusing politics, public sentiment, and commanders detached from their troops.

Since the Vietnam war era, the honor of being a US Military veteran, and the entire military establishment, has had its status impinged, recovered, and diminished repeatedly. Some of the questioning of the value of the American military was earned, some imposed unfairly. The sixties revolutionaries brought attention to the nation’s unfairness, and that insight included a high-resolution criticism of an American war machine that welcomed blacks as grunts but resisted ascension of those blacks into command and technical roles.

But that has reversed dramatically. In my travels over the course of twenty-three years in the US Army Reserve, and overseas duty attached to active-duty Army units, I was continually amazed at the number of black officers-company grade, field grade, and even general officers. Legions of enlisted senior non-commissioned officers who were diligent, disciplined, and enforced the same on their units. Combat leaders, operations staff, pilots, JAG officers, technicians; one of my good friends reached the rank of Command Chief Warrant Officer. CW5 is the highest of the warrant officer ranks, and it is small segment of the officer corps, and are the technical experts of the Army, and Chief Doctor provided IT and system administration support for a large segment of US Army Europe. His, and the great achievement of other African Americans in uniform means nothing to his community, and he is not a conservative by any means, my friend is a supporter of the democrat agenda. Therefore, my disappointment at the lack of interest . . . until we become a tool for you to use to complain about ‘him’ (the president) has made me cold to your complaints.

But that has reversed dramatically. In my travels over the course of twenty-three years in the US Army Reserve, and overseas duty attached to active-duty Army units, I was continually amazed at the number of black officers-company grade, field grade, and even general officers. Legions of enlisted senior non-commissioned officers who were diligent, disciplined, and enforced the same on their units. Combat leaders, operations staff, pilots, JAG officers, technicians; one of my good friends reached the rank of Command Chief Warrant Officer. CW5 is the highest of the warrant officer ranks, and it is small segment of the officer corps, and are the technical experts of the Army, and Chief Doctor provided IT and system administration support for a large segment of US Army Europe. His, and the great achievement of other African Americans in uniform means nothing to his community, and he is not a conservative by any means, my friend is a supporter of the democrat agenda. Therefore, my disappointment at the lack of interest . . . until we become a tool for you to use to complain about ‘him’ (the president) has made me cold to your complaints.

I also see hidden (or not so hidden) animosity at America at its heart, seeing us as sentient non-thinking drones fooled by the ‘white man.’ We know what we signed up for, most of us believe in it. I see the manipulative narratives offered to deconstruct the most effective fighting force the world has ever seen. The United States military is a victim of its own success, kind of like that infamous water well you don’t miss until it dries up. The American war machine has been so dominant that most of the population has no idea what it took to get it where it is. The military is taken for granted almost always, sometimes maligned for its culture, and occasionally castigated for not being a tool of this political end or that.

In our latest conflicts, Kosovo and Iraq and Afghanistan, it seemed to me that our strategy was not victory, but some kind of something else. A wishy-washy employment of enough intimidation and violence to achieve something . . . not quite a decisive military victory, but something else. We wanted to achieve national objectives without getting criticized by the rest of the world. We wanted to impose American will on another country without them being mad at us later for using our military might. That wishy-washiness persisted after departure from Iraq, the confusion of Benghazi, and culminated with the mismanaged and infuriating Afghanistan pullout, combining to devalue the public confidence in and respect for our military. It all combined to which effect recruiting which fell dangerously lower year after year.

But recruitment shot through the charts with the election of Donald Trump, and the appointment of Pete Hegseth to Secretary of Defense. Morale has improved, retention is higher, and i f I had known this was coming, I may have stayed in longer. But I’d had enough of the social agendas imposed by leftist politicians and the resulting mandatory briefs and training that had nothing to do with winning wars, that were forced upon the Army by politicians unfamiliar with military culture. The pendulum of American life affects all of this, and while the military is a fixed establishment, the relentless attempts to shape the nation’s warfighting machine to meet the whims of ‘the times’ and not the exigencies of destroying America’s enemies on a violent battlefield are just as dangerous as hostile forces.

f I had known this was coming, I may have stayed in longer. But I’d had enough of the social agendas imposed by leftist politicians and the resulting mandatory briefs and training that had nothing to do with winning wars, that were forced upon the Army by politicians unfamiliar with military culture. The pendulum of American life affects all of this, and while the military is a fixed establishment, the relentless attempts to shape the nation’s warfighting machine to meet the whims of ‘the times’ and not the exigencies of destroying America’s enemies on a violent battlefield are just as dangerous as hostile forces.

As a member of that fighting force I advanced into danger, staring through binoculars leading convoys through hostile territory and being shot at, I have a soft spot for my beloved fighting machine and all the good it has done in the world, solving problems that most do not fully understand. Yet I am able to look at the profession of arms objectively, to see where it falters, where it can improve.

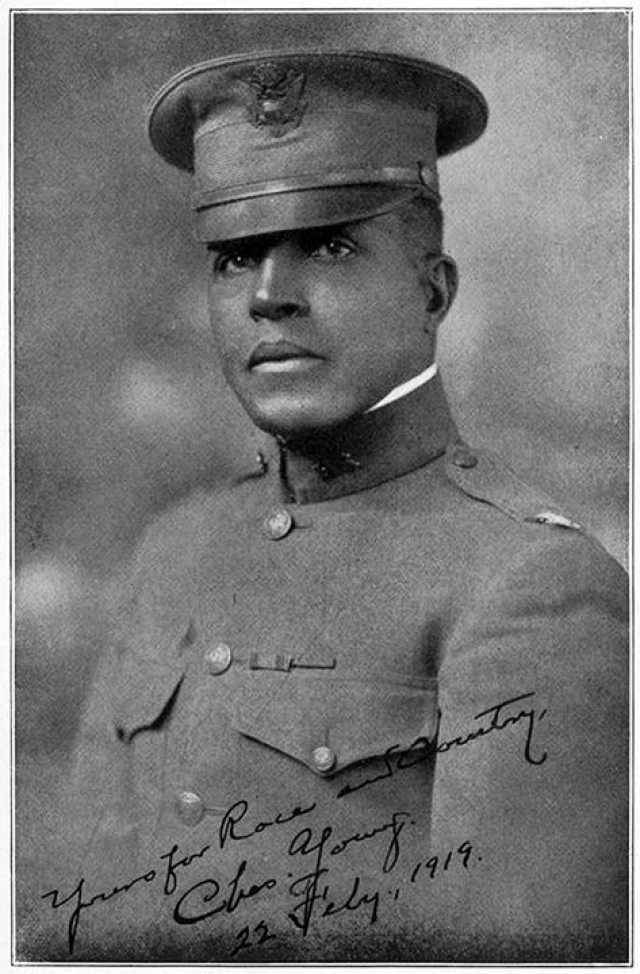

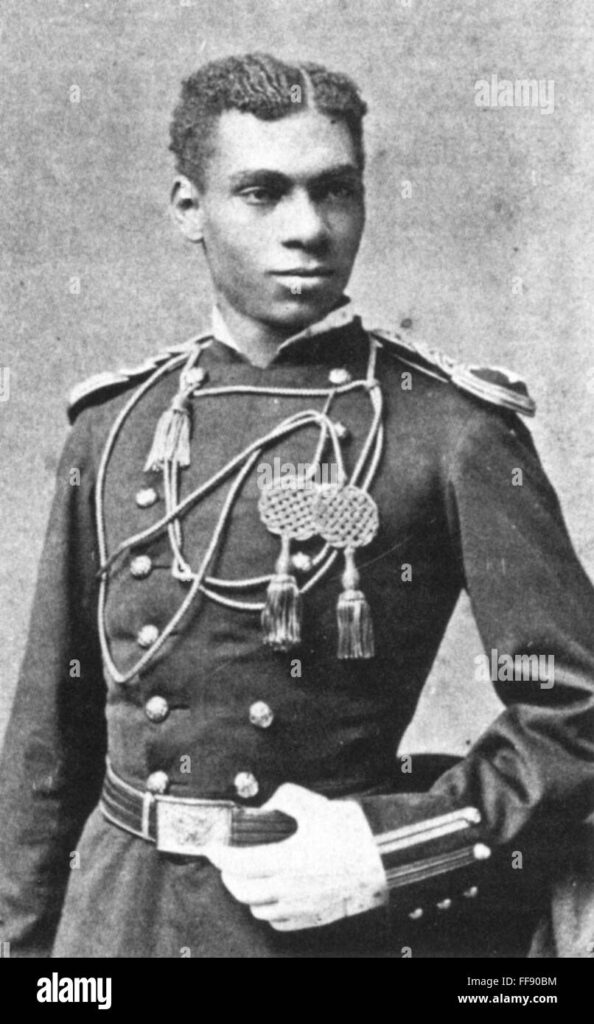

Most Americans, regardless of race, would probably not be able to name any important historical military figures, especially the younger generations. But blacks who claim to want positive role models, wouldn’t be able to name three prominent or important black servicepersons.

They know the dead rappers and gang members and who’s testifying at Diddy’s trial though.

Fake love.